Who is In, Who is out, Who is about?

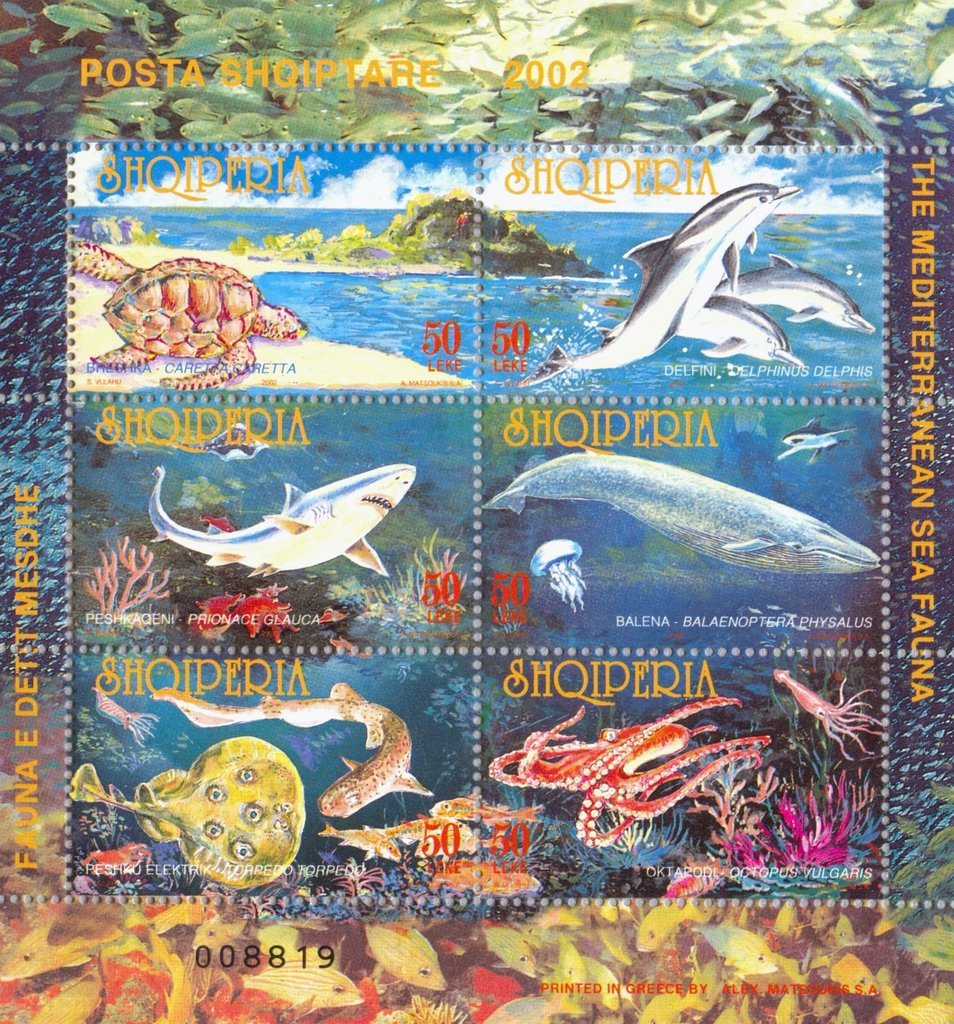

Looking at the Balkan area geographically, with a peninsula being a “piece of land almost entirely surrounded by water but connected to the mainland on one side”, let’s see what happens if we apply this definition to the Balkan States. Lands bordering the Balkan States in the North, Northwest and Northeast are Hungary, Italy and Moldova. Seas surrounding the Balkan States are the Adriatic in the West, Aegean in the South, Ionian in the Southwest and the Black Sea in the East. If we agree on the definition of the peninsula, then let’s look at who the current countries are on that peninsula and then their unique philatelic issuances. The former part appears to have an audience with varying opinions.

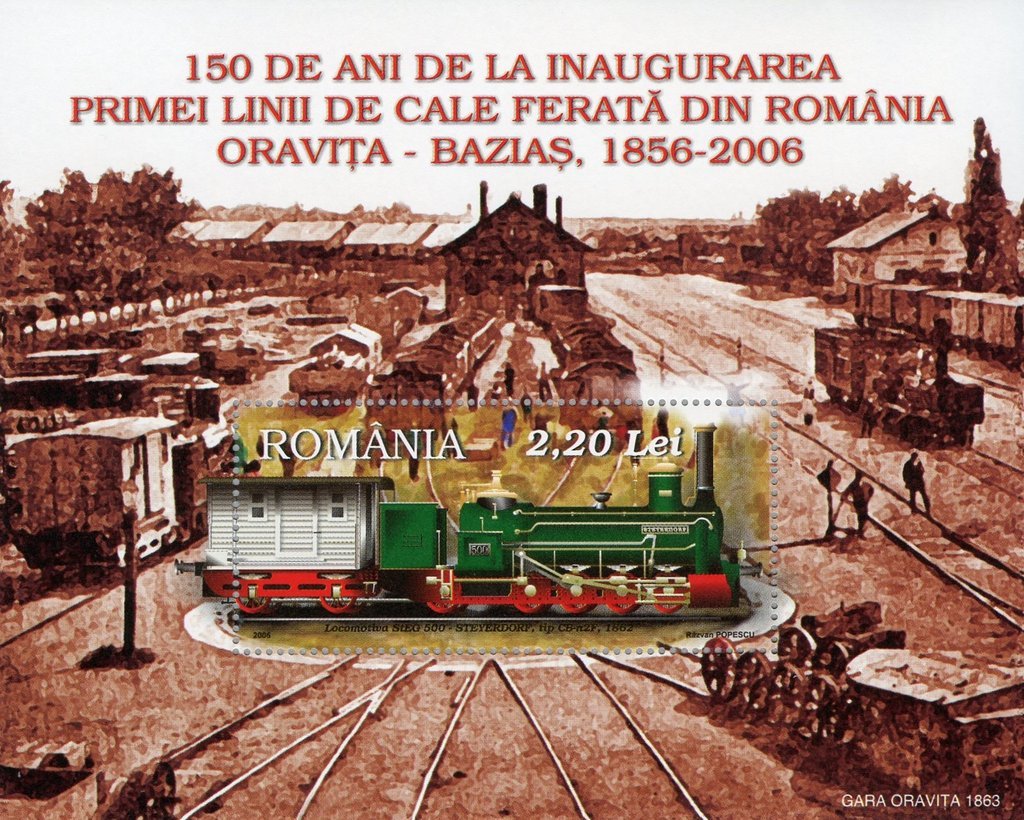

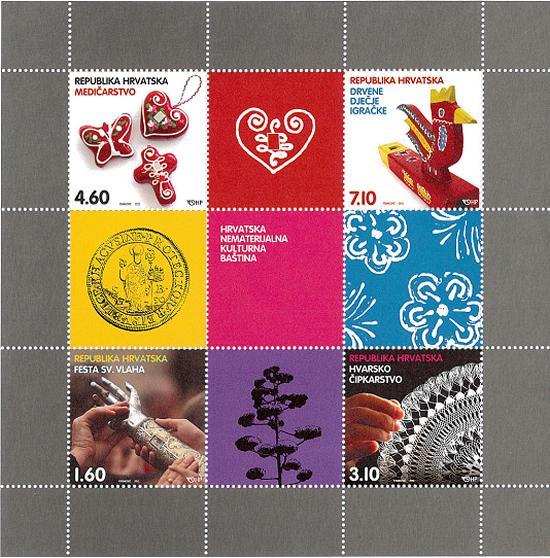

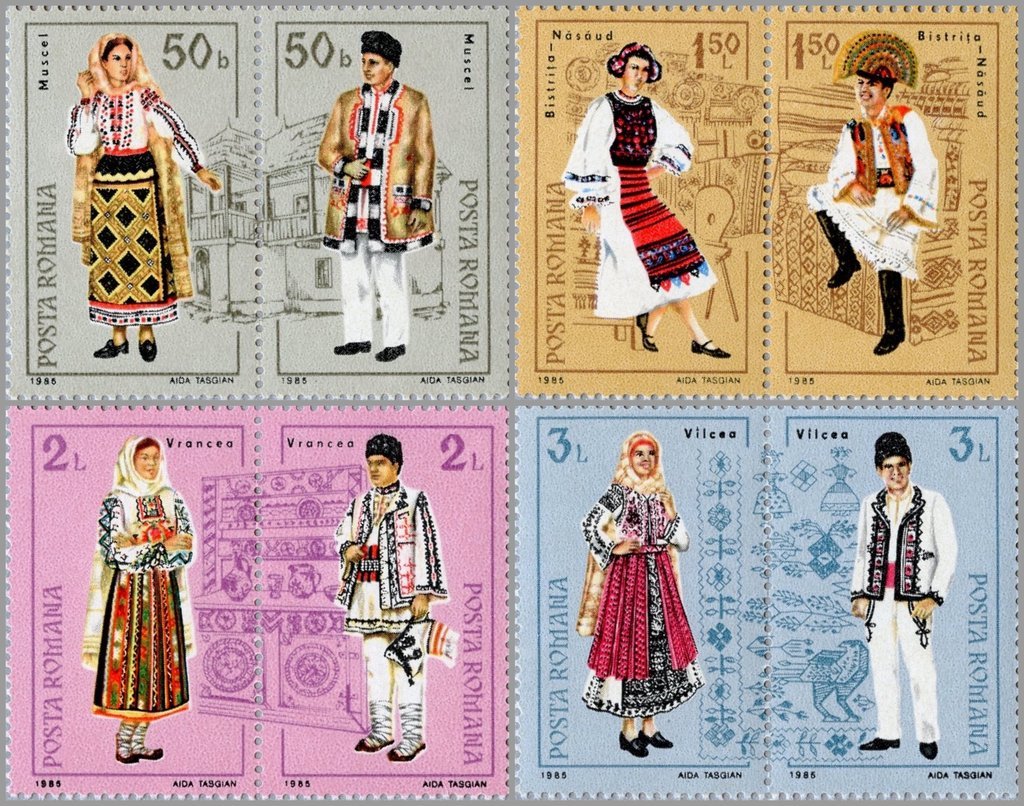

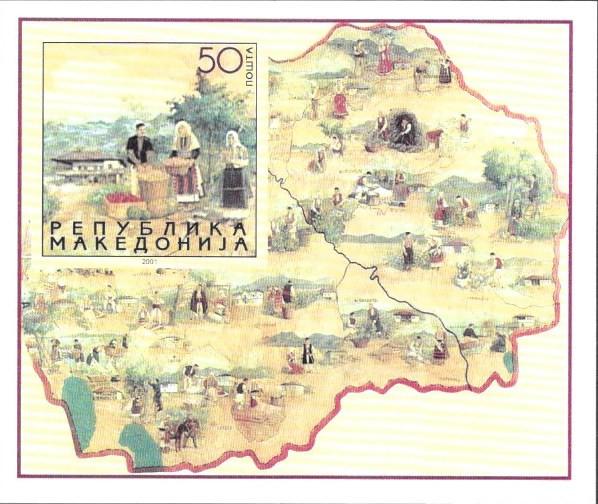

Our premise here at HSE is to include the following countries into the Balkans: Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia Herzegovina, Serbia, Romania, Montenegro, Kosovo, (Republic of North) Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece and Turkey.

While some people may choose to exclude Greece and Turkey from the Balkans because only part of these countries actually sit on the peninsula, with only half of these two countries residing on the peninsula, both have played major roles in the development of the Balkan States. Besides, who could possibly deny Turkey being a Balkan country when the name Balkan is Turkish for mountain?

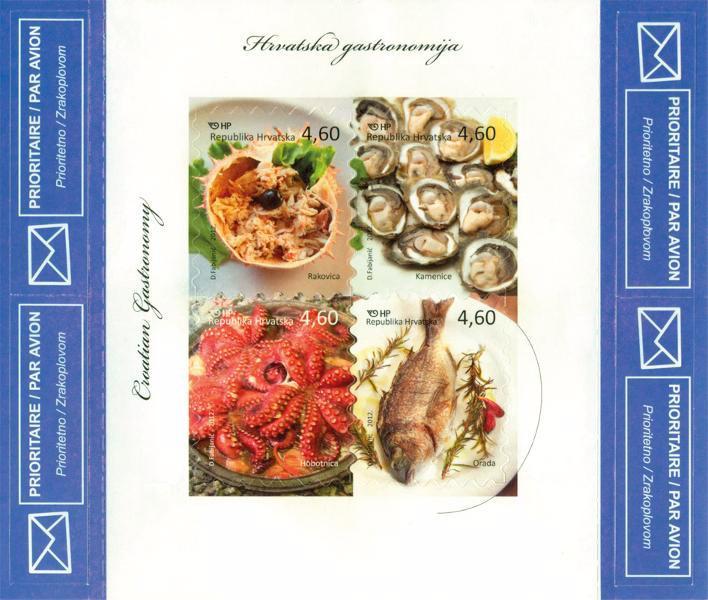

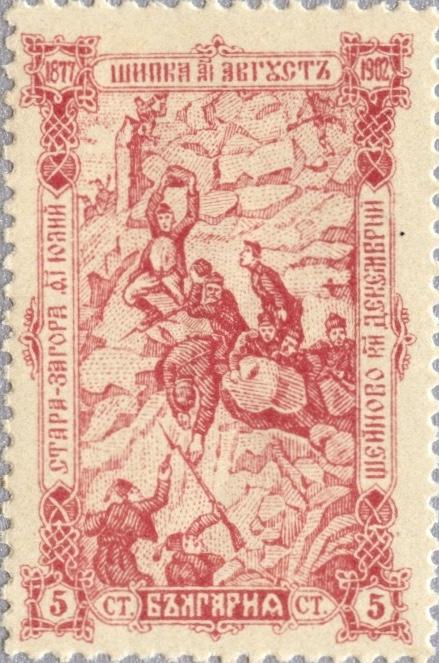

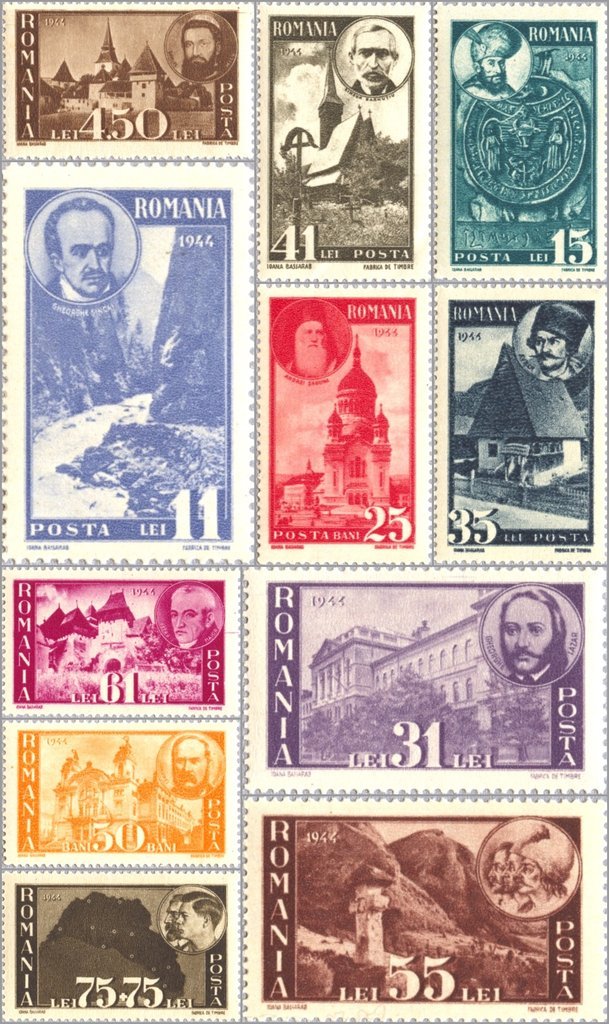

The Balkan States or The Balkans have been described by some people historically, culturally or along ethnic lines. The rugged terrain of the mountains, the containment of the four seas combined with the ethnic and cultural diversity of the people of the Balkan peninsula create an eclectic presentation in the amazing stamps of Eastern Europe.

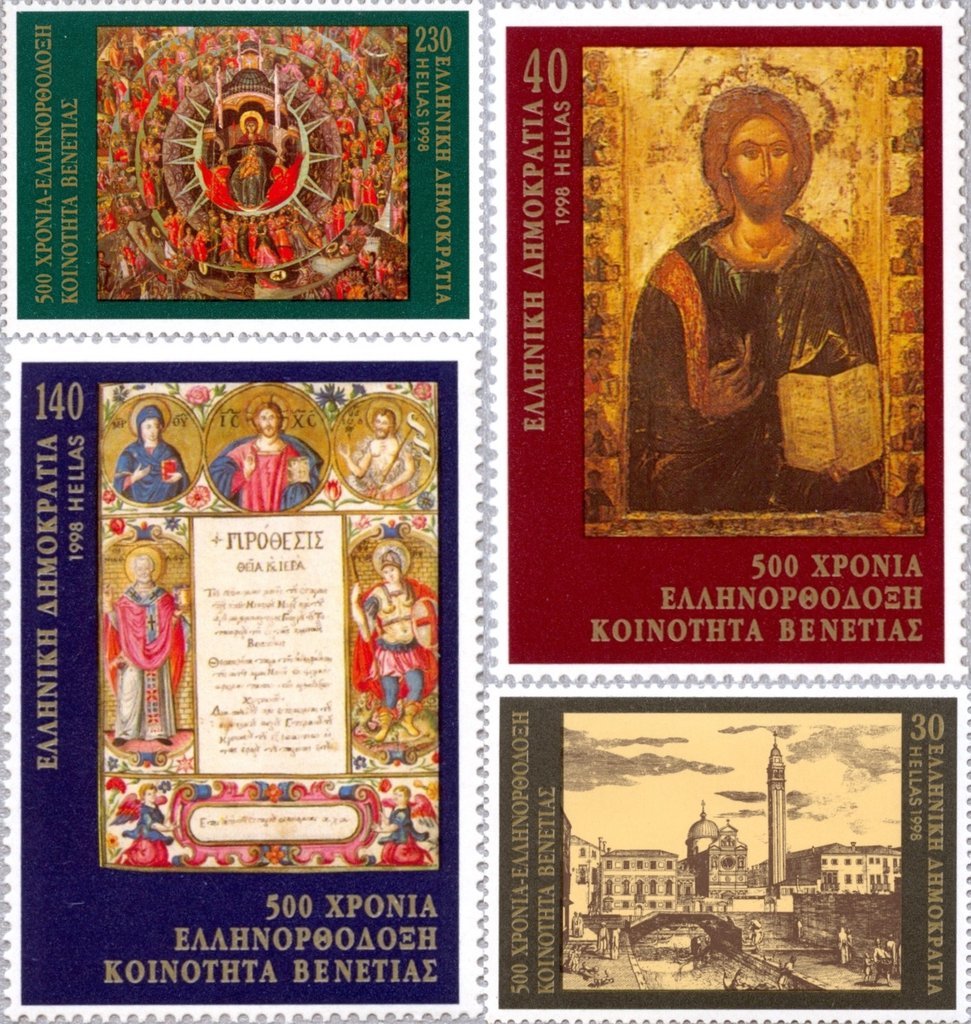

We hope you enjoy this philatelic adventure with us, viewing the variety and richness of the stamps of the Balkan States which reflect the cultures, religions and natural resources of this region. We here at Hungaria Stamp Exchange are pleased to offer stamps from all these countries which should be exciting to both country and topical collectors.

Early settlements in the Balkans on the West were created by the Illyrians and to the East by the Thracians. The Thracians intermingled with the Greeks but mountain terrain kept the Illyrians mostly separated. Not until the Roman invasion of the entire Balkan peninsula were the Balkan people united in a common legal and political system with military security.

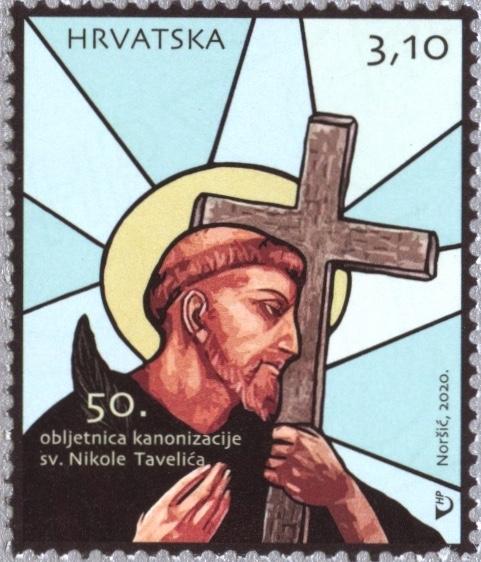

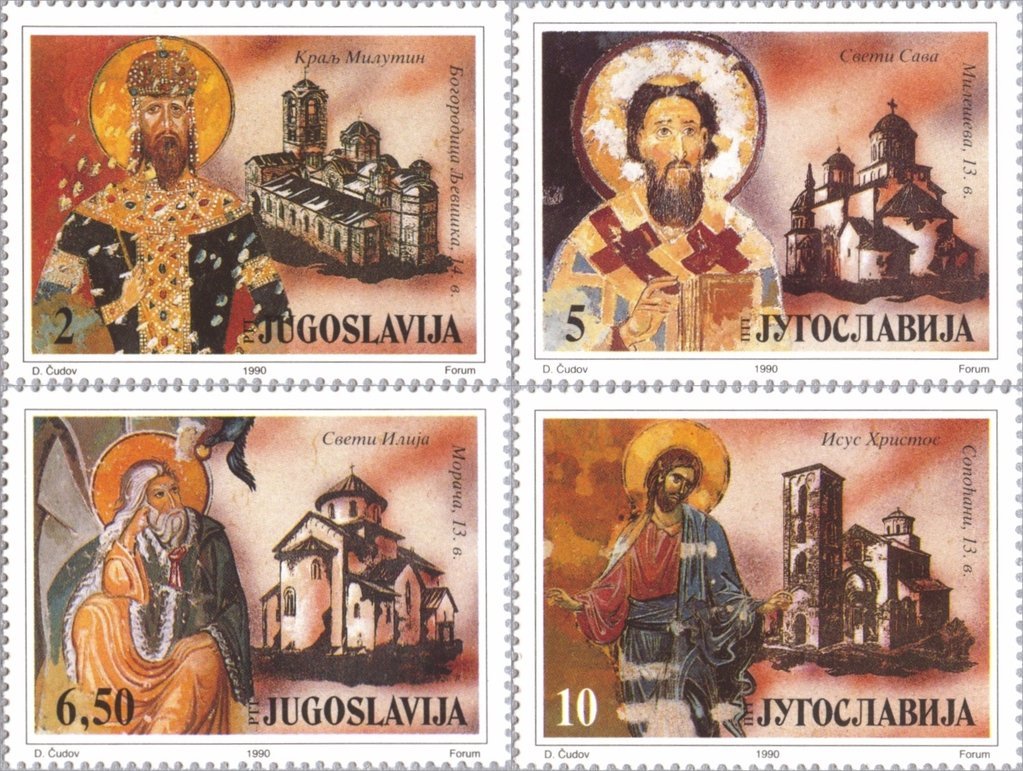

Christianity became the official religion near the end of the 4th Century and soon after the empire was divided into two Christendoms. The Western sector was under Roman influence and the East was ruled by the Byzantine. Invaders during the 5th century either left or were assimilated except in the case of the Slavs, staying to settle and cultivate the land. The Slavs then separated into four main groups: Slovenes, Croats, Serbs and Bulgarians.

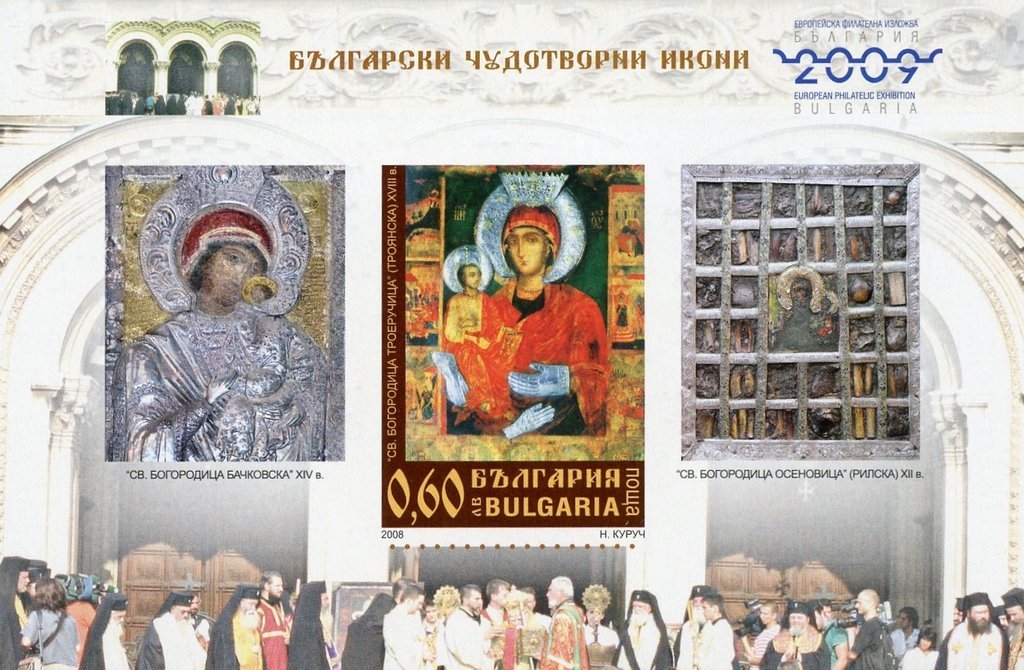

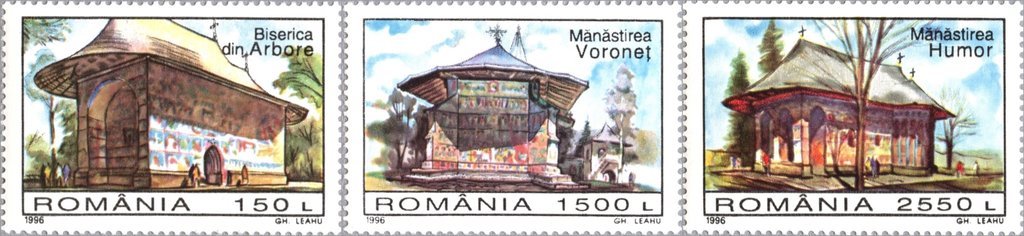

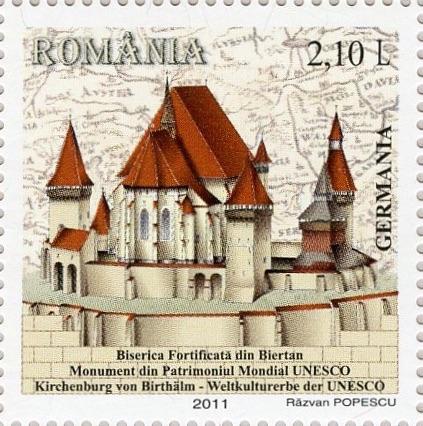

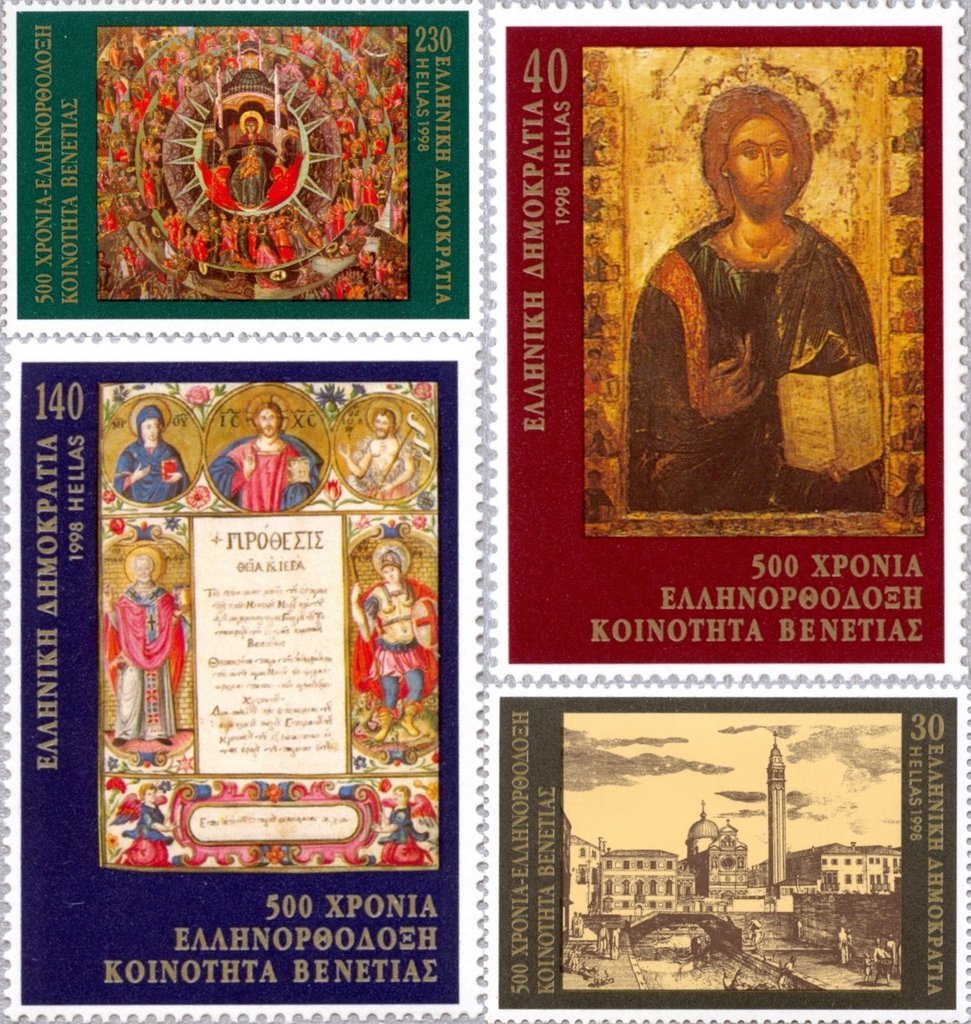

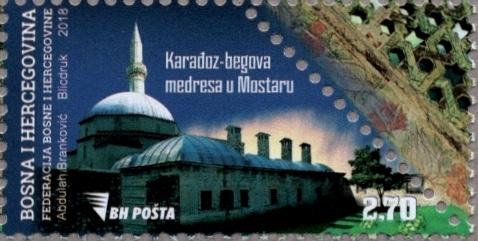

The Byzantine (Eastern) sector of Christianity was chosen by the Bulgarians, Serbs and Romanians joining the people of Greece in their devotion to Eastern Orthodoxy. The Croats and the rest of the former Roman Empire became part of the Western Christian community. Albania, isolated by the Albanian Alps Mountain chain, remained unaffected by Christianity. As you can see, the churches and monasteries of the Balkans are beautifully depicted on the stamps of the Balkans.

Within the Orthodox world two monks, Cyril and Methodius devised an alphabet to translate religious texts into Slavonic. This alphabet enabled the establishment of a liturgical and literary language for the Balkans, with Greek remaining in use in commerce and the administration of the Byzantine Empire.

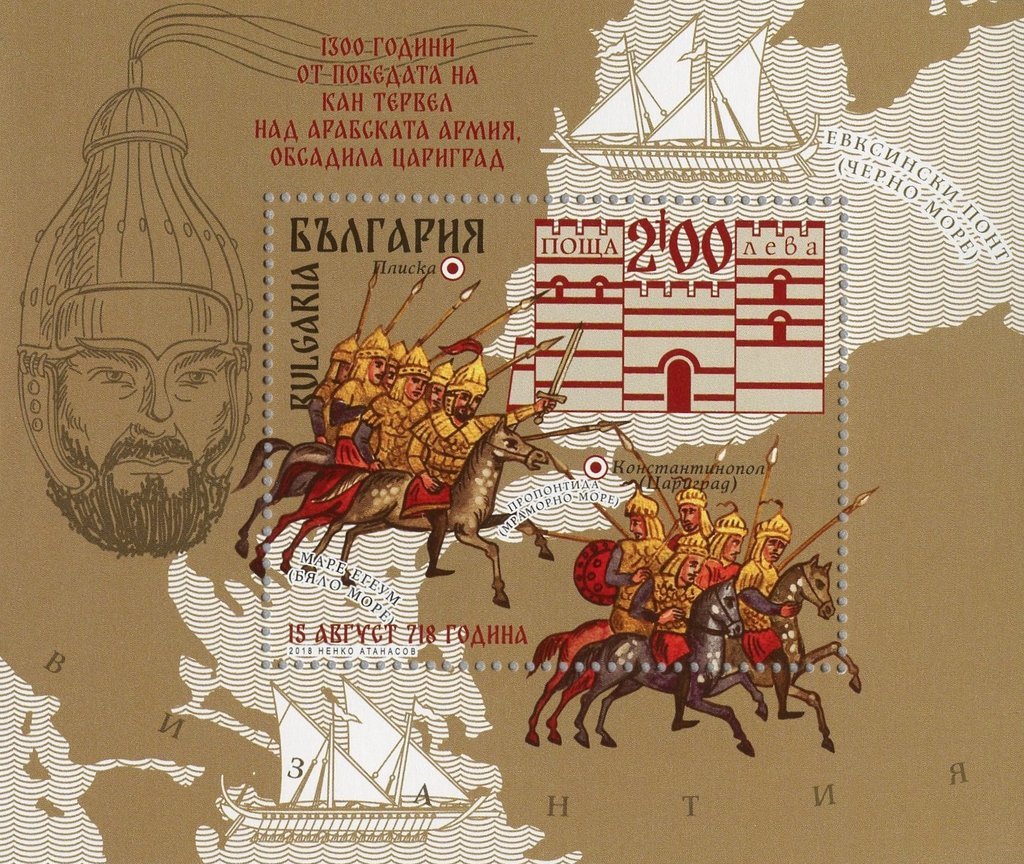

Byzantine military power rested upon landlords who held property in return for furnishing troops in time of war. The Byzantines developed a rather corrupt civil service which weakened the strength of the Byzantine Empire. Starting with conflicts between the first Bulgarian empire and Constantinople, later threats came from the East from the Muslim Seljug Turks in the early 11th Century at the Battle of Manzikert. A century later, the threat came from Western Crusaders who seized Constantinople holding it for five decades.

The Crusades increased the hatred of Eastern Orthodox against Westerners and Catholics. The weakening of the Byzantine Empire allowed Venetians to dominate seaborn trading in the Eastern Mediterranean, however with the Slavs not uniting together, Byzantine control continued. In the 14th Century, Serbia ascended in power above Bulgaria when Stefan Dusan became king, providing a legal code and conquests.

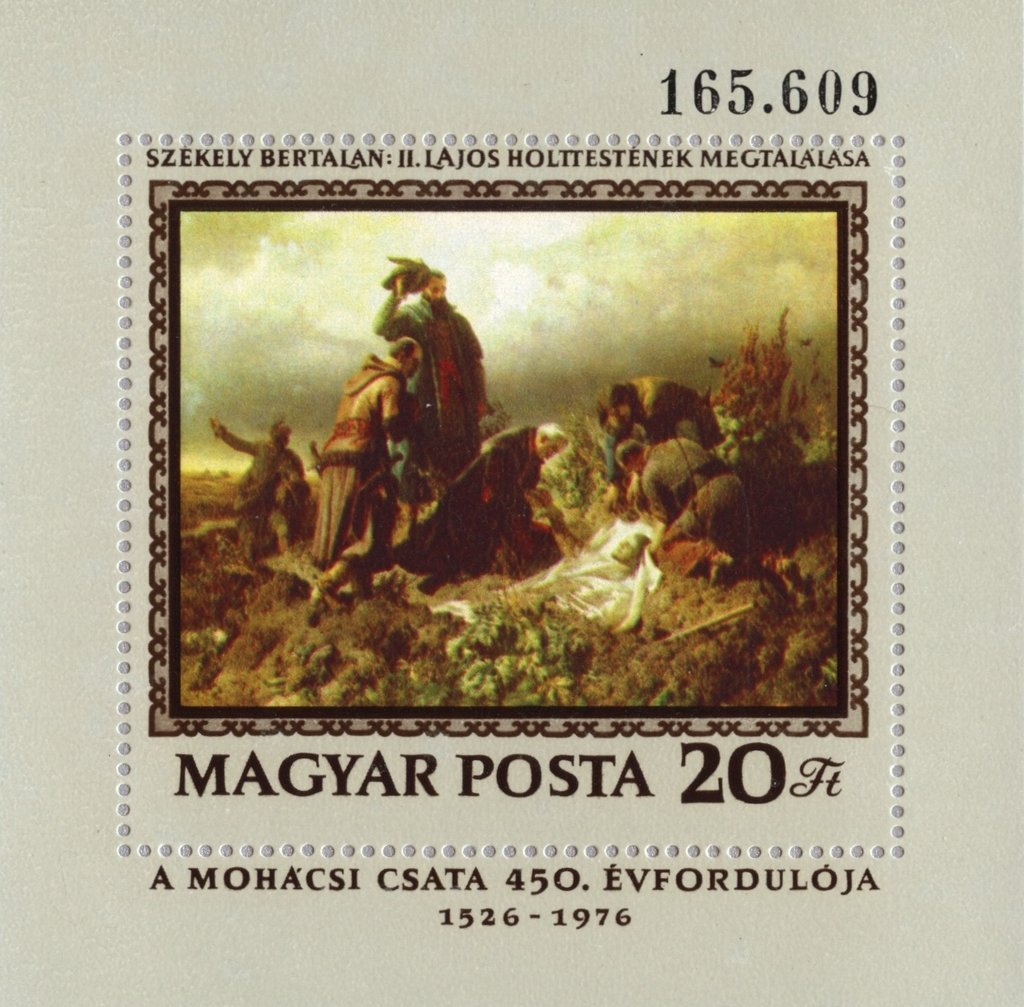

While various Balkan states fought among themselves for a while, the real danger emerged from the south. Starting in the mid 14th Century the Ottoman Turks began their conquest of the Balkan peninsula which took a century to complete. The Ottomans marched northward until they defeated the Hungarians in the Battle of Mohacs.

Successful in the north, Ottoman power was more diluted in the western area. Transylvania, Moldavia and Walachia and Montenegro acknowledged the suzerainty of the sultan, head of the Ottoman Empire. The trading center of Ragus (modern Dubrovnik, Croatia) remained independent while Bosnia and Albania converted to Islam, enabling them to keep their land holdings. The irreversible decline of the Ottoman Empire in the late 17th Century and the encroachment by Austria and Russia in the last two decades of the 18th Century led to the collapse of central government in the Ottoman Balkans.

Frustration over the weakness of central government rather than over its overbearing presence produced a Serbian uprising of 1804, the first successful Christian revolt against Ottoman rule.

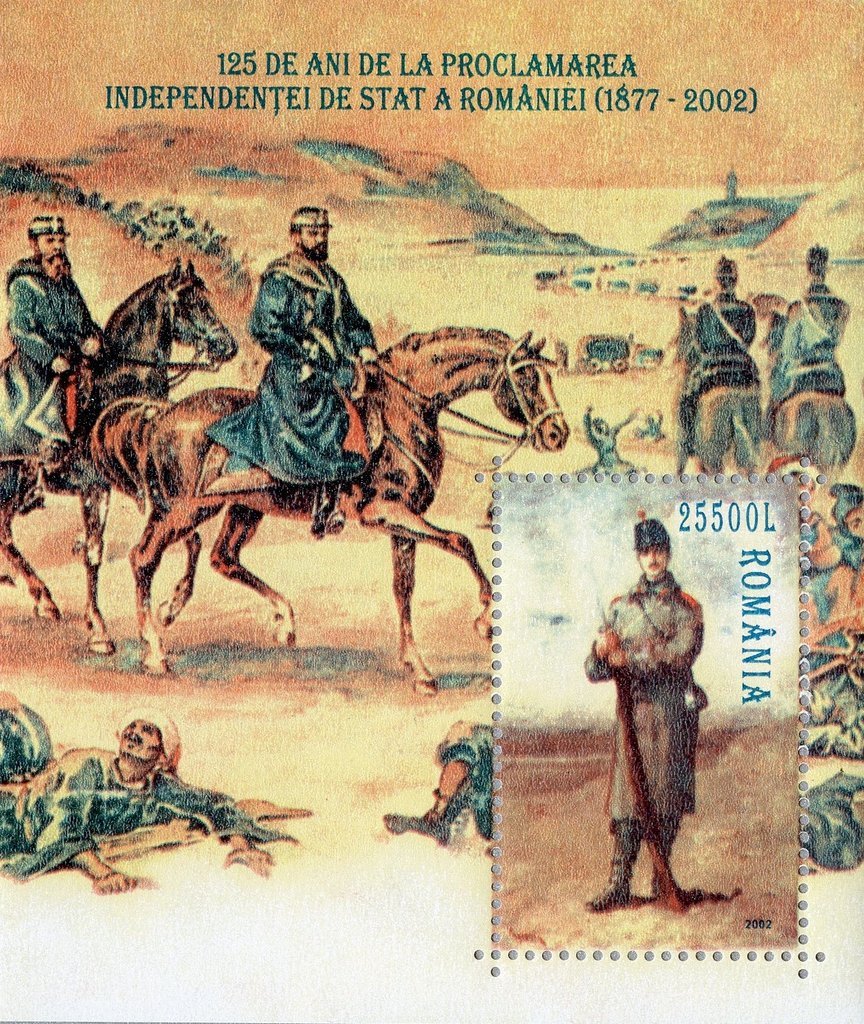

The 19th century gives rise to the creation of nation-states in what had previously been Ottoman territory, made possible only with external support for independent statehood. National identity has been preserved in the Balkans through folklore and folk song and is well depicted on stamps. Epic poetry of Serbia kept alive the memory of Dušan, Skanderbeg, and others.

A sense of national identity also survived as a result of Ottoman power being concentrated in the towns. Villages were largely Christian leaving Christian customs mostly unaffected by Islam, the religion of the Ottomans. Religion played an integral part in preserving national identities. Even in the first violent years of their conquest, the Ottomans seldom touched monasteries, where relics, icons, books, and other cultural treasures were zealously guarded. Preservation of religious traditions provided continuity with their non-Muslim past.

External forces also played a major part in determining the Balkan States that were created. The states were required by the Western European powers to be monarchies with constitutional rights and protection of minorities. Once the new Balkan states were established both before and after WW l, they attempted to build political and economic structures based on the West. This effort was hampered by their own histories with population shifts continuing in the Balkans into the 20th century. After the Ottoman conquest, Ottoman Muslims moved into Albania, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia. This population influx included former prisoners of war, freed slaves, converts and some migrants from Anatolia (Asian Turkey). Further ethnic relocations and violence perpetrated by both Ottoman forces and Christian rebels occurred cause Muslims to leave in large numbers.

Ethnic shifts occurred for all major religious groups. After the creation of the Bulgarian state near the end of the 19th century, Muslims left and Christian refugees arrived from Macedonia and Thrace. Russia’s Jewish population moved into Bessarabia, Moldavia and Walachia through the 19th century. At the end of the 19th century Armenians fled the massacre to find safety in Bulgaria. When Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina at the start of the 20th century many Muslims moved into Macedonia and Thrace. Between the Balkan Wars through WWl there were population exchanges between Bulgaria and Greece.

The creation of independent states was somewhat disruptive of ethnic patterns and traditions. Political boundaries did not coincide with these ethnic divisions. Shepherds might now have their flocks separated from their summer pastures or from access to their markets for sale. Traditional fairs which were the basis for trade were disrupted as were churches and monasteries, separating them from some of their parishioners and land.

The Balkan states emerged separately and at different times. Each had claims to further territory they considered to be theirs by ethnic or historical right making a Balkan union or solidarity unlikely.

Although the trigger for WWl was the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne by a Bosnia Serb nationalist, no Balkan state originally wished to become enmeshed in World War l. Once conflict was forced upon the peninsula, individual states reluctantly joined at different times. Although having no desire for the conflict, the Balkan peoples could not escape its consequences. All suffered serious economic consequences and dislocations and mass troop mobilizations resulted in severe casualties. Everything from the requisitioning of draft animals to food created problems for the villages and many trade connections were ruined.

When World War l destroyed the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, the fate of their Balkan possessions Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vojvodina, Slovenia, Bukovin and Banat of Temesvar, Transylvania and Bessarabia had to be decided by delegates at the Paris Peace Conference 1919-1920. Inevitably settlements did not completely follow ethnic lines. While the rationale may have been well intentioned, the creation of larger states being stronger economically and more resistant to Russian communism, it created many very ethnically mixed populations some of which did not speak the same language.

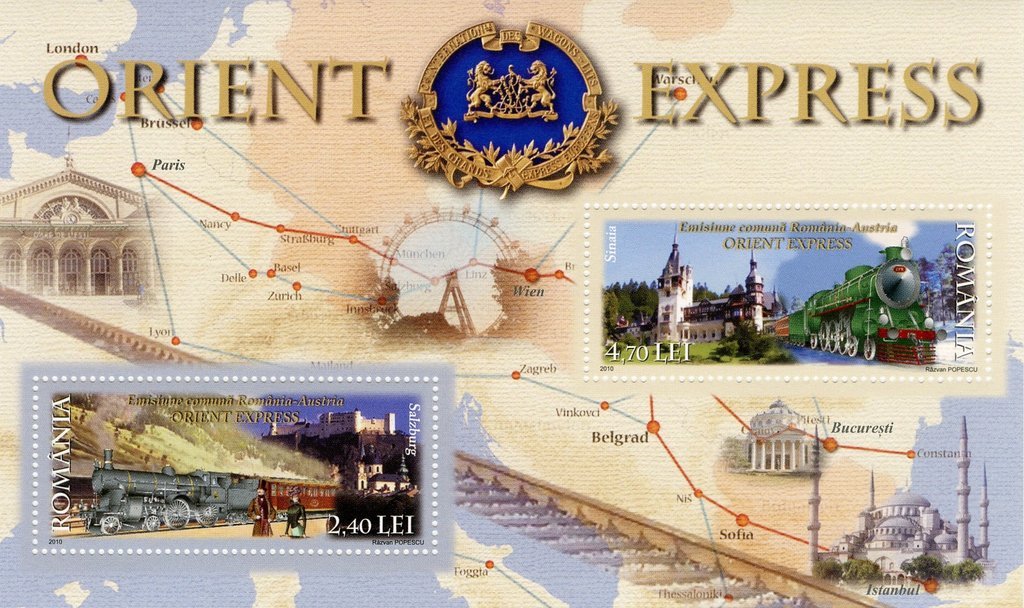

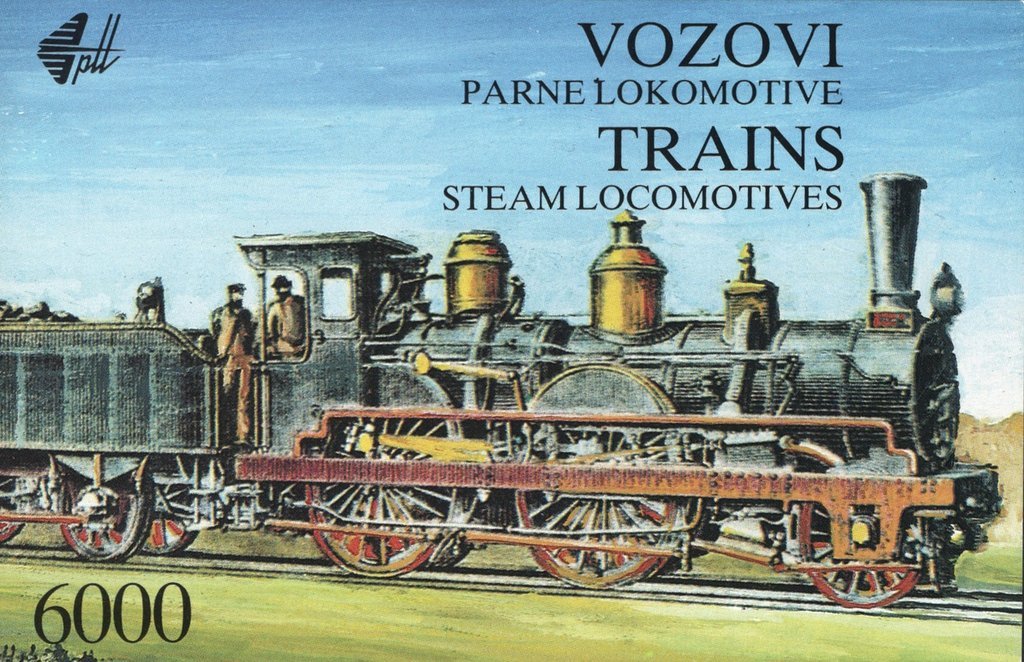

Where railways had existed they served the need of the old empires rather than the new states, some even having a different gauges. Legal codes, currencies, taxation systems needed to be unified. Integration was more complex as the territories involved developed differently.

Yugoslavia as a country was formed in 1918 immediately after World War I as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes by union of the States of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Kingdom of Serbia. Later, the government renamed the country leading to the first official use of Yugoslavia in 1929, planning for it to become a single state for all Slavic people. Yugoslavia was comprised of the current Balkan states of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, (Republic of North) Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo.

While this union was extremely effective as a union against Soviet Communists, a national Yugoslav identity never emerged with each separate state retaining its own ethnic identities and cultures. An example of these ethnic identities can be found in the example of the current day three postal administrations of Bosnia and Herzegovina. While one country, the Postal Authorities and their corresponding unique philatelic issuances are Bosnia Muslim, Bosnia Serb and Bosnia Croat.

Ottoman controlled areas were subject to the sultan’s laws, customs and wishes. States from former Austro-Hungarian Empire or Russian Empire had a more sophisticated intelligentsia, functional bureaucracies and economic infrastructure. Land reform was a large issue. In Romania large estates were broken up and many other Balkan states soon followed. Stability started to return to the peninsula. Fear of Russian communism led to outlawing the communist parties in all Balkan states. Except for Albania, internal stability returned within the next decade.

Soviet Communist controlled Balkan states did not solve the issue of Nationalism in all the Balkan States after WWll. Several ethnic groups in many of the Balkan states were given minority states and in some cases their customs restricted, such as for the Albanian population in Yugoslavia, the Macedonians in Bulgaria as well as the Roma people and the Hungarians of Romania. Two decades of Communist control of the Balkan states did not bring about an improved living standard, but did bring more restrictions on ethnic customs and local culture. Stamps issuances during the Soviet area had a utilitarian look and many times served as propaganda for Communist control.

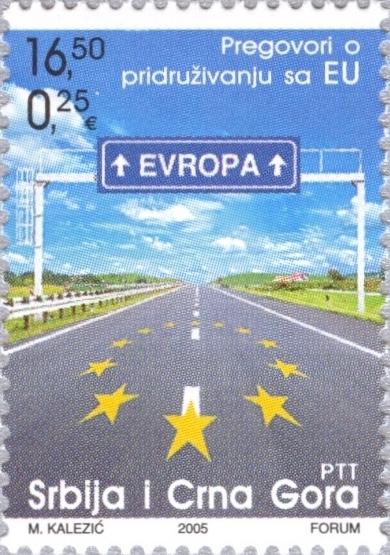

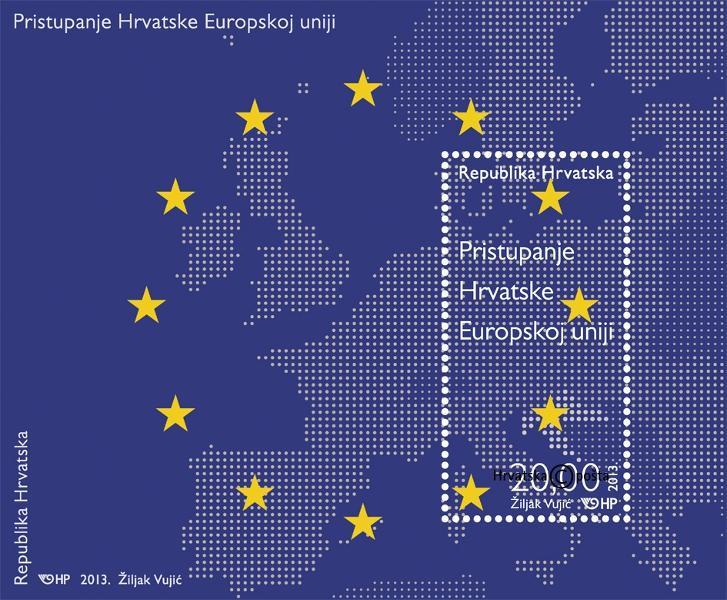

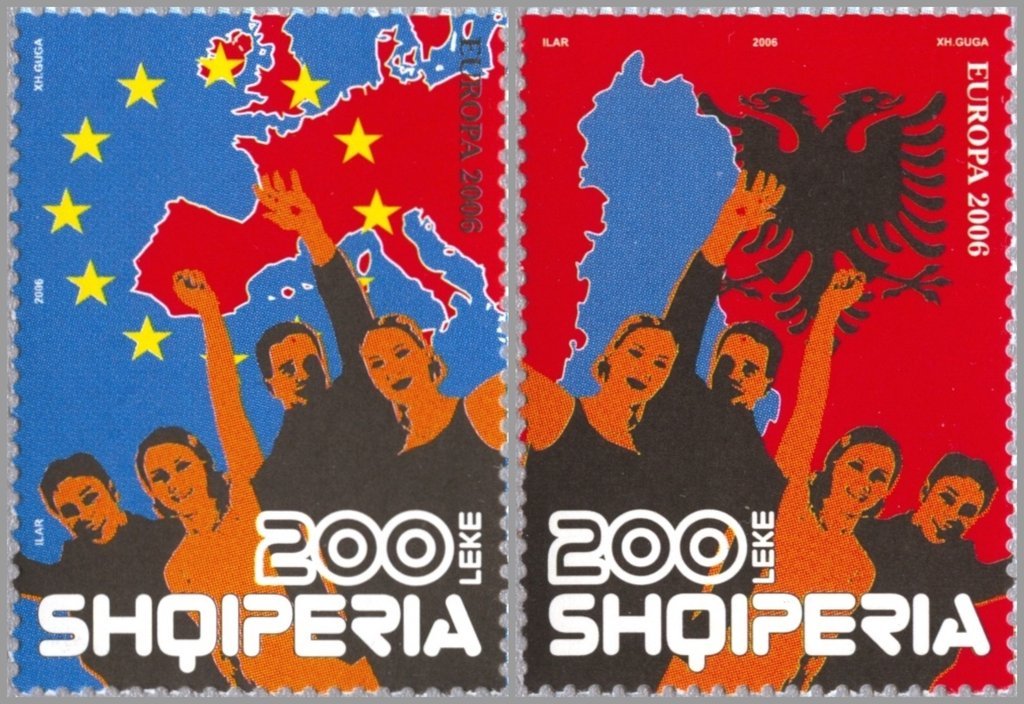

By the end of the 20th Century, independent Balkan states emerged, sometimes after experiencing violent civil wars based on ethnic identities. The various Balkan States had found their way out of Soviet controlled authoritarian governments, and each faced the similar challenge of building a competitive economy in the world.

Most eventually associated with the European Union and the World Bank. At the close of the first decade of the 21st century, the prospects for peace, stability, and economic prosperity for the peoples of the Balkans improved significantly. NATO and the EU expanded their influence in the area by offering membership to an increasing number of Balkan States.

We believe it is evident that the stamp issuances of each of the Balkan States reflect the uniqueness of their respective cultures and religions. The dynamics of the Balkan peoples have persevered and evolved to meet the challenges of today’s world. We hope you enjoyed sharing our whirlwind trip around the Balkans states as reflected through their distinctive philately.